When we walk into a space, we ask and determine what we can do in that space.

We scan the environment, which in its design/structure/furniture helps us produce inferences that allow us to come to provisional answers to these questions.

Space is never neutral. It whispers messages about what can and will happen here and, being attuned to the affordances and constraints, we are obliged to follow antecedent regularized forms of participation and action found in such a space.

— Why Space Matters to Creativity – Wendy Newstetter, Director of Learning Sciences Research, College of Engineering (retired) – Georgia Institute of Technology. In 2012, with support from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the LSC undertook a project focusing on Cognition and Context: How Space Affects Learning and Creativity in the Undergraduate Setting. Newstetter was a member of the Sloan project team.

“How can the principle of choice be leveraged into planning and designing high-performance settings for learning?”

This is the question we ended with; we did not begin with it. We started with a lot of discussion about students, about the experiences of students as learners, and about the potential of empowering the principle of ‘choice’ for students.

The idea of the principle of choice is when the individual student has a role in making choices about their settings for learning. Having this choice makes the student feel big in comparison to the institution as more choices are available and settings become less prescriptive. This phenomenon relates to the idea of building community, of creating a naturalness of access, of spaces that are not intimidating but rather spaces that signal to students that they can make choices, of spaces in which students have the option to form communities from within and not be dictated to from without.”

In 2010, the Learning Spaces Collaboratory (LSC) was organized to continue and capitalize on efforts of the PKAL community focusing on spaces for learning. Gathering the sense of the community was the initial step to establish a foundation for the work of the LSC.

A cadre of PKAL-active academics and architects convened to imagine that future. Based on their collective experiences in imagining and shaping spaces for 21st century learners, four “prompting” questions to drive planning and assessing such spaces were identified:

In 2013, an LSC Guide to Planning and Assessing 21 Century Learning Spaces for 21st Century Learners was published. The featured section of this Guide was a series of case studies from campuses illustrating how such prompting questions serve as a framework for realizing spaces that enable institutional goals for what learners are to become.

In 2016, the LSC began hosting a series of onsite regional Roundtables, designed to capture responses from a small gathering of academics and architects to the prompting questions:

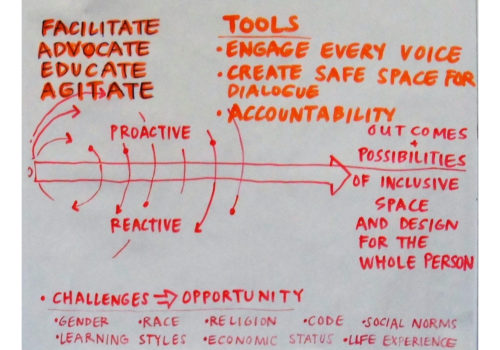

In 2023, questions surfacing from some of these earlier Roundtables are of particular value. At the 2016 LSC Roundtable at the University of Washington, in the context of focusing on issues relating to inclusivity, the beginning questions such as these went back and forth among the academics and architects:

LSC Roundtable Collection I: Essays on Designing for Inclusion and Equity

I. FROM PKAL VOLUME I. SHAPING THE FUTURE—WHERE LEARNING HAPPENS.

Serendipity—the chance discovery of an idea—is common in the daily practice of science and mathematics.

Facilities need to support serendipity, to have spaces spread through where spontaneity can be exploited on the spot through informal discussion with peers, using a computer in a common study hall, or doing late-night laboratory teamwork.

Colleges and universities need spaces for science that will support a blend of teaching styles linked more tightly to the laboratory, space that encourages interdisciplinary uses of major instrumentation, and classrooms wired for multi-media presentations and computing. Computing…must be persuasive: students and faculty must have access to computing where they work and learn.

Science and mathematics are increasingly social, as opposed to solitary, activities. Our buildings must reflect this social character of science and mathematics by providing spaces for exchanges between faculty and students.

A department needs also to consider seriously the “hospitality” of its space for students and its role in fostering community. With certain restrictions, the science building should be accessible and useful to students after normal business hours. This type of environment develops a learning community and pays rich dividends in learning, and in the persistence and recruitment of students into science.

(Presented at the 1st PKAL National Colloquium, at the National Academy of Sciences, 1991)

Findings from Research & Practice – What Works in Planning for Assessing Learning Spaces

Decades of research on creativity and innovation suggest three basic levels of analysis: the individual, the group, and the organization. Each of these levels tends to be studied by different scholars within different disciplinary traditions—for example, individual creativity is studied by psychologists, whereas organizational creativity is typically studied by management scholars in schools of business.

Because creative work in organizations always involves individual factors, group factors, and organizational factors, the Learning Spaces Collaboratory is interested in research at all three levels. There is substantial evidence that learning—often considered to be a solitary, individual act—benefits from group interaction. If our goal is to prepare graduates to contribute effectively to our modern innovation economy, they need to be prepared to participate in highly collaborative creative environments—because this is the reality of creative work today.

Creativity Research Findings at Three Levels of Analysis – Keith Sawyer, Morgan Distinguished Professor of Educational Innovations – The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Education

University of Wyoming Michael Enzi STEM Education Facility – Research Facilities Design